Learn

Our post-COVID recovery: Investing for a sustainable future

11th May 2020

From crisis comes opportunity. From a (hopefully) once-in-a-generation pandemic has come the chance for once-in-a-generation investment in recovery. We need to get this right, not only to kick-start economic recovery but also to meet future challenges.

Our post-COVID recovery: Investing for a sustainable future

From crisis comes opportunity. From a (hopefully) once-in-a-generation pandemic has come the chance for once-in-a-generation investment in recovery. We need to get this right, not only to kick-start economic recovery but also to meet future challenges.

Paying back the debt resulting from this recovery is a burden for the younger generation. We need to ensure that government and private sector investments are addressing future challenges, including climate action, achieving greater equality and building resilience to future shocks.

Initial stabilisation measures have focused on ensuring there is sufficient liquidity, through Reserve Bank quantitative easing and the wage subsidy. These have helped ensure confidence in the financial system and maintained the link with employment for those employees and businesses experiencing disruption. Different policy tools will be required for recovery.

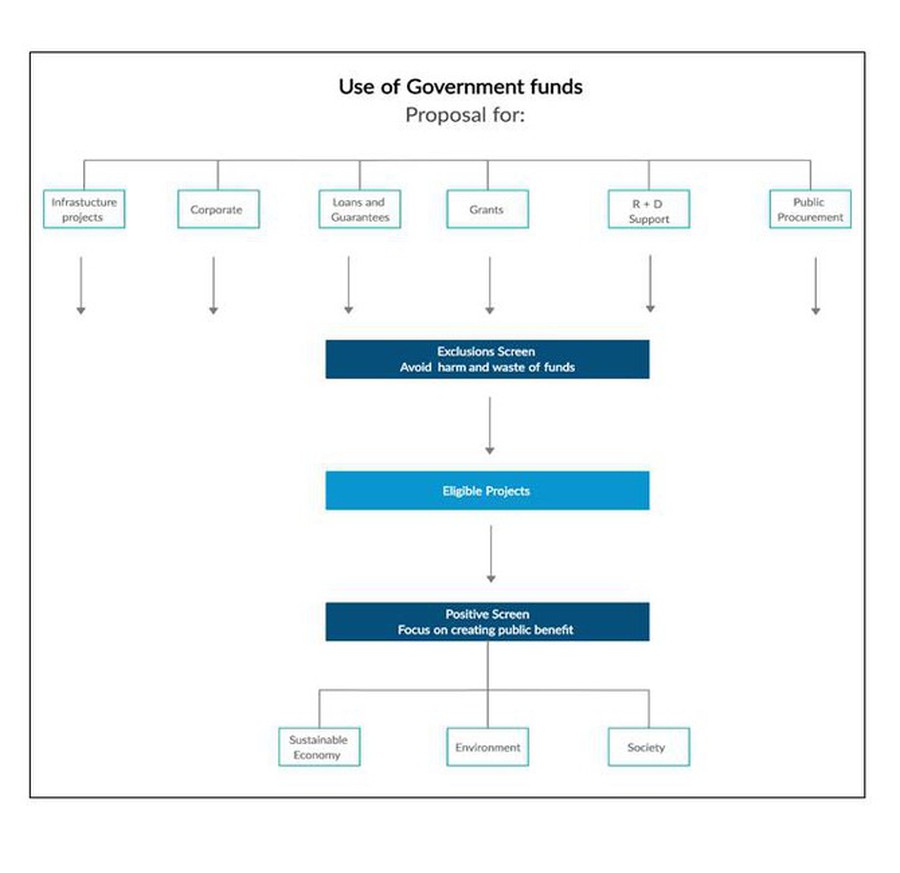

A responsible investment framework could be used to ensure that government investment focuses on those companies and projects that generate the highest possible benefits and avoid wasting public funds.

Raising our gaze

In the recovery and rebuilding phases, it will be tempting for the government to spread funding around businesses and workers that have suffered a downturn. However, the most effective use of funds will come from having a clear framework that screens out some businesses and projects, and targets most funding to those that not only create jobs, but also generate positive benefits that will enable us to build back better.

New Zealand has rightly gained international respect for our approach to managing the COVID-19 crisis. It has been focused and effective, and it has built shared purpose throughout society. We should set a similar level of ambition for the economic recovery package. The aim should be to improve sustainability and wellbeing for all New Zealanders, now and in the future.

The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, has said: “Everything we do during and after this [COVID-19] crisis must be with a strong focus on building more equal, inclusive and sustainable economies, and societies that are more resilient in the face of pandemics, climate change, and the many other global challenges we face.” This is our chance, perhaps our once-in-a-generation opportunity, to get it right.

The Framework for Wise Use of Public Funds

A clear framework is needed for the massive public investment programme ahead. The absence of a robust approach was obvious in the Global Financial Crisis. The US government lost $10 billion in the bailout of General Motors and far more in hand-outs to Wall Street. Reports of continued high bonuses to Wall Street traders left a bitter taste. In New Zealand, we had our own costly bailouts, including $1.6 billion for South Canterbury Finance.

The government is caught in a dilemma. If they don’t impose conditions, they risk wasting money. Wage subsidies have resulted in questionable subsidies paid to businesses that won’t survive and/or don’t need the money, including those that have been paying high levels of dividends and excessive salaries to executives. Public scrutiny has been levelled at a long list of companies including strip clubs, wealthy law firms, meat processors, golf courses owned by overseas billionaires and large businesses such as SkyCity, Fletcher Building, Restaurant Brands and Summerset Group.

Although quick-disbursing grants, such as the wage subsidy scheme, played an important role in the early stages of the crisis, the reality is that tough choices need to be made in the next stage. Some businesses and even whole sectors will not survive. Government cannot continue untargeted, ‘no strings attached’ funding.

However, if government imposes conditions that are too onerous, businesses will be unable to participate or unwilling to do so. Just $23 million of the $6 billion of government-backed loans under the Business Finance Guarantee Scheme have been taken up so far. And if the government uses discretionary approaches without a robust framework, they will be accused of ‘picking winners’.

A clear and objective framework is needed. The government must ensure best use of recovery funding by being clear about what activity it is not going to fund, and which types of companies and projects deserve scale up support. This will deliver long term public benefit as well as recovery.

Investing responsibly

The good news is that tools to differentiate between companies are now available. Over recent decades, there has been a huge rise in responsible investing, at least partly driven by the recognition that fund managers can reduce risk by avoiding companies that do not adhere to acceptable social, environmental and governance (ESG) standards. The investment sector has developed tools that support investment managers to differentiate between companies.

Some form of responsible investment now covers 72% of New Zealand’s professional managed assets under management and over $90 trillion of global funds managed by members of the Principles for Responsible Management (PRI). This framework not only manages risk but is often used as a proxy for public benefit. This framework can be used by government to allocate funding towards the highest public benefit.

Exclusions screen

The first stage in the screening approach is a ‘negative screen’. Most investment managers avoid investments in sectors like tobacco and particularly harmful weapons such as nuclear arms, landmines and cluster munitions. The latest annual survey of public attitudes towards responsible investment shows that three quarters of the public do not want their funds to be invested in these companies and others including gambling, pornography, fossil fuels and companies that damage the environment and violate human rights.

In the case of COVID recovery, screening out these companies would avoid projects and companies that create social and environmental harm. Funding should not be provided for companies that operate in harmful sectors (such as predatory lending or gambling), use unethical practices (such as underpaying migrant labour or polluting the environment), or breach acceptable norms (such as Treaty of Waitangi obligations). Companies using their corporate structure to avoid paying tax, or with operations in tax havens should also not be eligible.

Screening can also identify sectors and companies that are incompatible with government policy. For example, funding emissions-intensive companies without imposing any climate conditions is not just a waste of taxpayers' money, it's also a recipe for further hardship, bailouts and stranded assets.

For example, there is a real danger that even more funding will be allocated to infrastructure projects that are ‘shovel-ready’, like low priority roads and bridges. This follows the government’s infrastructure package in the last budget that allocated most of the $12 billion to roads. This would be short-sighted in an era of climate change, at a time when businesses across the country are discovering the benefits from remote working. Roading projects are capital-intensive, create relatively few jobs and lock us into a carbon intensive future.

A similar screen is required for other fiscal policy instruments, including loans and loan guarantees, grants, preferential government procurement, R&D support and bailouts. In addition to ESG screening, tests of viability and need are required. Some of those businesses are not fit for the future and will be unlikely to survive the recession. Others do not need the funds, as has been evident from the long list of examples of companies that have returned their wage subsidies after adverse publicity.

The framework combines this negative screen to avoid harmful impacts and waste with a positive screen to focus on achieving public benefit.

Recovering with Positive Impact

So far, most of the discussion of recovery has focused on retaining jobs, but it should be recognised that not all jobs are equal. As we have seen, some create social or environmental harm. Others generate public benefits. The wise use of public funds requires a focus on the projects and companies that will deliver the highest impact in terms of public benefit.

The tools of impact investing provide a framework for assessing impact according to broad benefits, such as greater equality, environmental regeneration, lower emissions and greater resilience. These are measures that are included in the government’s wellbeing framework – they should now be used to identify and scale up positive impact.

While the impact investing sector is still fledgling in New Zealand, international impact funds have gained experience in identifying and growing businesses, social enterprises and charities that deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals, emissions reductions to meet the Paris Agreement and the Living Standards Framework.

There are several impact funds that have recently been established in New Zealand, so far available only to professional investors, and the new Green Investment Finance, a new government-funded initiative that provides catalytic funding to businesses that reduce emissions. Mindful Money aims to support the development of a range of impact funds that are available to members of the public, so that investors have the opportunity to generate positive impact from their investment.

Crucially, many of the most attractive opportunities for private investment are not yet viable because government policies do not provide the right incentives. For example, the carbon price is still capped by the Emissions Trading Scheme at a level of $25 per tonne, far below the real costs of climate emissions. A World Bank analysis of recovery programmes from the Global Financial Crisis showed that mis-pricing externalities and a lack of financial incentives was a major impediment to investment by the private sector. This is the most cost effective way to generate public benefit from private sector investment, and it needs to go hand-in-hand with the recovery programme.

There is no shortage of ‘shovel ready’ investment opportunities available to the government. This is the time to upgrade our public services, broadly defined. Proposals include a fast rail system; improved walkways and cycleways; protecting our native forests, rivers and oceans; education and training for future work opportunities; strengthening the resilience of the health system; building affordable housing; decarbonising our energy system and insulating homes; adapting to climate change; and supporting the transition towards a more regenerative agricultural system.

A just transition is as necessary for the COVID crisis as it is for the climate crisis. Additional funding should also support those in need through funding for mental health and the caring sector, including community organisations and NGOs; increasing the level of benefits; supporting those unemployed to retrain; and repairing the holes in our social safety net. Building back better needs to mean improving equality and ensuring the inclusion of all our people.

Putting the framework into practice

There has been no shortage of advice on what the government should fund. However, there has been far less discussion on the criteria. This paper offers a robust framework for recovery and re-build to identify what not to fund, as well as where to focus public investment. It draws on tools used extensively in the investment sector, and links them to measures of public benefits such as the wellbeing framework.

As well as suffering and loss, we have discovered unity, caring and kindness through this crisis. These values, and our innate strengths of innovation and a can-do attitude, will be needed to meet the challenges ahead.

Barry Coates is Founder and CEO of Mindful Money